Former `Lost Boy’ shares his journey from Sudan to Baldwin

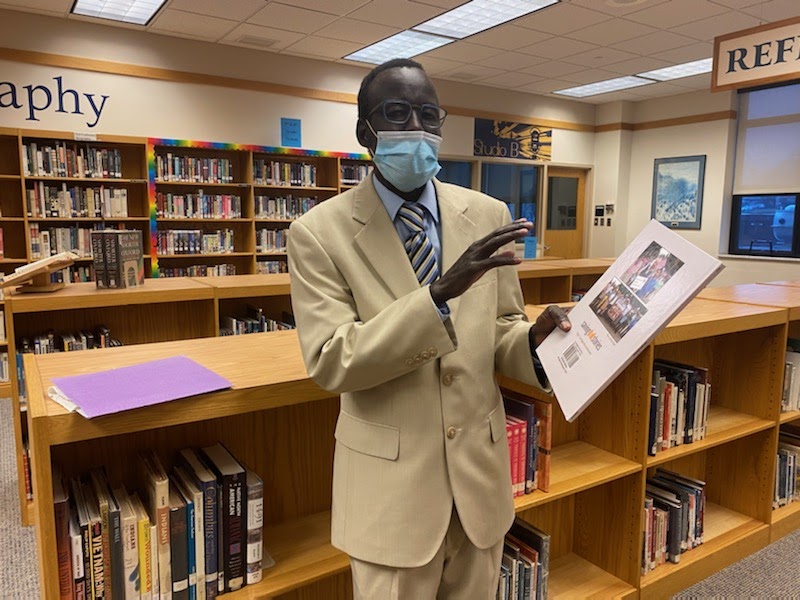

Gabriel Ajang, who at age 9 became one of the “Lost Boys” of Sudan, shows the children’s book he has written. Ajang spoke to Honors English 9 students after they read a magazine article about the Lost Boys.

December 6, 2021

Gabriel Ajang faced many life-threatening struggles when he was 9 years old and was forced to flee his village as one of the Lost Boys of Sudan, but one of the more terrifying was his encounter with a lion.

While walking along a path with a 7-year-old friend, Ajang spotted a lion. It raced across the path once, then turned back and ran across the path twice more. Ajang instructed the younger boy to remain still and as calm as possible until the lion left the area.

“I was scared to death,” Ajang said Monday in a presentation to Honors English 9 students, who recently read a magazine article about the Lost Boys. He remembered thinking at the time, “God don’t let me die by being eaten by a wild animal.”

From the beginning of his journey fleeing the civil war in Sudan in 1987 to when he finally reached America and found a home in Baldwin-Whitehall in 2001, Ajang faced dangers and obstacles from disease, hunger, attacks from the Sudanese military, and years spent in refugee camps in two different countries.

He was born in Sudan and lived a happy life in a peaceful place until the civil war reached his village in 1987. Ajang was doing his daily duties, caring for the cattle, and when he heard gunshots and saw smoke in the distance near his village. He and other boys decided to hide in the woods until dark.

“We were not going home because the home had been bombed and destroyed,” Ajang said. “Many children lost their families, and lost contact with their families.”

Ajang had lived happily with his five siblings and parents until that day.

“I lost my parents that day. My brother, later on, I found out he landed in a different place,” Ajang said. A sister also survived, but the three siblings are the only ones left from his family.

Eventually the boys – as well as some girls, and a small number of adults – began walking. Later they started walking at night to avoid bombings from planes and the dehydrating weather. But animal confrontations were common in forests at night.

“The lion, the hyena, the wild dog you see at the zoo – they are very real out there,” Ajang said.

Eventually they crossed into Ethiopia, where they lived at a refugee camp for about four years. But in 1991, a new Ethiopian government forced the Lost Boys out. Ajang and his group were forced to run away again.

They escaped from Ethiopia back briefly into Sudan, this time taking a different route that led them to a river that was difficult to cross and infested with crocodiles. The day after Ajang made it across, the river flooded. Many crossing the river that day drowned or were attacked by crocodiles, leaving the survivors with more sadness.

“You know if you don’t see that person, they’re gone,” Ajang said.

The Lost Boys eventually made it to a second refugee camp, in Kenya, where Ajang stayed for nine years, until he was 22 years old. Malaria and other diseases threatened them at the refugee camps, he said.

Finally, on June 6, 2001, Ajang landed in Pittsburgh.

“We didn’t believe it, but it happened,” he said.

Ajang gives credit to all the volunteers who helped him and his Sudanese friends achieve their goals.

He settled in the Baldwin-Whitehall community and took on his first job as a busboy at what was then the Hilton Hotel downtown. In 2001 he earned his GED, and then he attended the Community College of Allegheny County before transferring to Slippery Rock University and graduating in 2007.

In 2008, Ajang was able to return to Sudan and was reunited with his brother after 21 years apart. He stayed in Sudan for 11 months and got married. He returned to Baldwin in 2009, although his wife was not able to immigrate and join him until 2012.

Now he and his wife have four children, three of whom are school age and attend Baldwin-Whitehall schools. Ajang works for the Department of Veteran Affairs in Oakland.

Baldwin students who attended the presentation said it helped them realize what intense struggles Ajang and the others from Sudan had encountered.

“It makes you realize how different we have it here,” freshman Mary Harmon said.

Georgia Holbert said that learning about Ajang’s story was moving.

“It makes us more grateful,” Holbert said.

Ajang, meanwhile, also has published a children’s book, Two Dinka Folktales, telling the stories he was told as a child. This book can be found in local community libraries, as well as on Amazon.

It has been a long journey, and he has learned many things.

“The main thing I want people to learn is that as individuals you can help,” he said.