The resurgence in the riot grrrl scene should be more inclusive

Tamar-kali is the essential segue into afro-punk music in the riot grrrl scene.

March 26, 2021

The riot grrrl scene of the 1990s and early 2000s is seemingly making a resurgence in feminist movements across younger generations.

Riot grrrl artists combined feminist and political issues — most specific to women — and inserted it into punk music.

While artists like Bikini Kill, Bratmobile and Hole were quite influential in their time, it’s important to remember that their music was fairly exclusionary, and only touched on the issues that affect white women. It even went so far that non-white listeners and artists felt like they didn’t belong in the movement. Riot grrrl eventually died out and a genre of Afro-punk rock was developed, sista grrrl riot. The irony is lost, however, because rock was mostly pioneered by black musicians.

Even the recent resurgence movies made about the subject, such as Moxie or The Punk Singer, only include music and issues from white artists, excluding women of color from these issues. It is true that black women face different issues than white women, but excluding them from the narrative completely is not the answer.

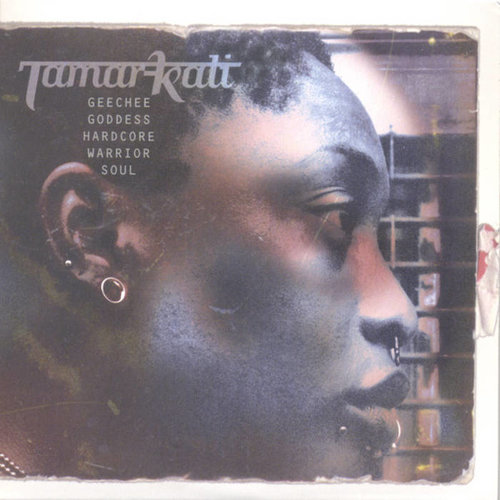

Tamar-Kali Brown was and is one of the most influential afro-punk singers in the riot grrrl movement. Her music was much overshadowed by groups like Bikini Kill in the original movement, but her music is a strong portrayal of issues specific to black women, and it’s a significant addition to the resurgence in this genre.

Brown recently has been writing music for movie soundtracks, but her EP Geechee Goddess Hardcore Warrior Soul from 2003 is most important to the riot grrrl scene of the 90s and 2000s.

Brown’s style is culturally significant because she relates to traditional African aesthetic, and punk served as an awakening for her to express herself this way. This is prevalent in her EP through her glaring portrayals of issues facing black women.

This EP deals with issues specific to black women. The first song, “Boot,” details the experience of the black woman by criticizing the inherent sexualization of young black girls and the way society manipulates them.

Most typical riot grrrl albums tend to follow this screechy and almost whiny sound, but Brown does the opposite and it truly makes her stand out. Brown has a soulful sound on this EP that is really not done much by punk artists.

This soulful sound is perhaps most prevalent in the song “Lover.” While this song is heaviest on the distorted rock riff, the vocals in this song are a strong portrayal of Brown’s soulful sound. She ultimately does an excellent job of portraying Afro-punk and her music is a good segue into listening to this sub-genre.

The resurgence in the riot grrrl scene has already proved to be more inclusive of artists like Brown, but still women are fighting for inclusivity. It is impossible to be 100 percent inclusive due to the infiltration of racism that unfortunately happens in the punk scene, but hopefully the new riot grrrl scene will do a better job of combatting this than in the past.

Feminism of course includes all women, regardless of race, and as the new age of feminism progresses, it is likely that riot grrrl will adapt as well.