Three fashion companies and some celebrities have come under fire recently for appropriating clothing, jewelry, and religious symbols from South Asian culture.

As a person of Nepali descent, I understand that there is a difference between appropriation and appreciation. However, in these instances, it is undeniable that the companies Oh Polly, Peppermayo, and VRG GRL were appropriating.

In the first instance, the United Kingdom fashion brand Oh Polly has been criticized after promoting a two-piece set that resembles a popular South Asian garment called a sharara, which is sometimes called kurta.

Many people are demanding that the company apologize and give credit to South Asian culture. So far, Oh Polly has yet to address the issue.

Oh Polly’s outfit is included in their Occasionwear: Invitation Only collection and marketed as “Embellished Convertible Lace-Up Gown in Floral Pink.” The ensemble includes a fitted short dress with floral designs stitched on, with a bottom that is a loose pink skirt.

People argue that the embroidery and basic design are too similar to South Asian styles.

The issue is not inspiration. Humans have exchanged cultures and practices since the dawn of time. The reason people are angry is because of the lack of acknowledgement of where the style came from.

Fashion brands like Oh Polly try to take these styles and rebrand them as something new. For a minority group like South Asians, that feels disrespectful to their history.

Beyond cultural erasure, the brand is also being called out for the dishonest pricing. The outfit, made mostly of polyester, is priced at $260. But similar designs – made with better materials – can be found at a fraction of the cost from South Asian-owned businesses. This dress feels like a cash grab, with the company profiting off unoriginal designs and ignoring the clothing’s cultural roots.

The Australian brand VRG GRL, meanwhile, came under fire when they added an earring to their website. The earring looked like a close replica of a traditional South Asian earring called jhumkas, to the point where the inspiration was undeniable.

However, the brand marketed the product as “Bohemian.” There was no mention of its cultural origins in the website.

After much backlash online, the brand issued an apology and took the product off their website.

Another brand that has come under similar scrutiny recently is Australia-based Peppermayo for their adaptation of the dupatta, which is usually a sheer shawl worn around the neck that is worn with dresses.

The internet community has branded it with the ironic term “Scandinavian scarf.” This is a reference to a similar controversy surrounding comments by Bipty founder Natalia Ohanesian, founder of the fashion rental company Bipty. Ohanesian referred to South Asian style sheer shawls as Scandinavian and “European effortlessly chic.”

People were quick to correct her, informing her that this kind of shawl is called a dupatta or chunni, and it is rooted in South Asian culture. Since then, the “Scandinavian scarf” has become a sarcastic meme in the South Asian community.

Even some Scandinavian women have weighed in, criticizing the misrepresentation. Many argue that labeling something that is clearly South Asian as Scandinavian doesn’t just erase South Asian identity – it disrespects both cultures.

While Ohanesian made an honest mistake, the incident brought attention to the normalized erasure of South Asian culture. The dupatta specifically evokes the most discussion.

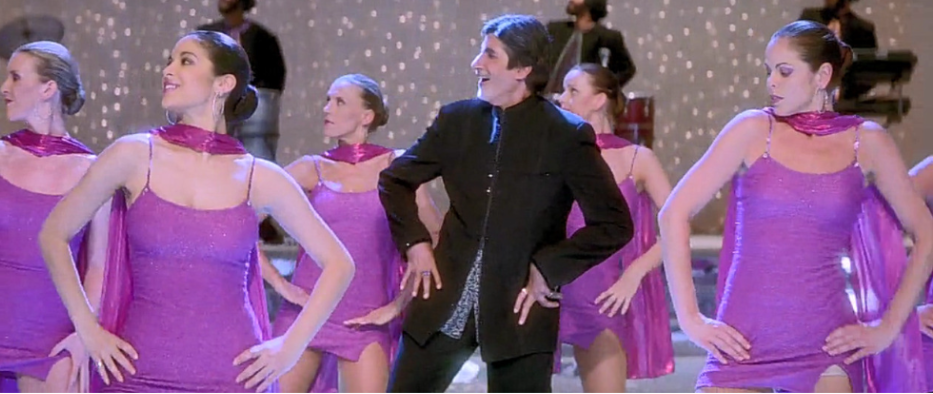

The dupatta has been a symbol of femininity and resistance for South Asian women for thousands of years. In the early 14th century, Rajput women would collectively throw themselves into a fire to avoid being captured by enemy forces. Before walking to their deaths, they would put their dupattas over their heads as a final act of dignity.

More recently, in 1984 Pakistani women burned their dupattas as a sign of protest against anti-women laws put in place by dictator Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq.

While dupattas are a cultural statement, bindis, which are also called tikas, are a religious symbol. A bindi is a dot in between the eyebrows where the Ajna chakra is located. It represents spiritual insight and intuition. Some may refer to it as a symbol of the third eye.

Gwen Stefani, Vanessa Hudgens, and Katy Perry were just a few of the people who commercialized the bindi to sell a more exotic look. People even referred to it as “Coachella makeup.”

Their fans tried to excuse their behavior by claiming “cultural appreciation,” but there are limits to what can be put on for the sake of appreciation. Would it be cultural appreciation if non-Christians wore the cross for photoshoots at a non-Christian event? No, it would just be disrespectful.

For many South Asians, the issue isn’t that their culture is being seen. It’s that the culture is being disrespected, misnamed, and repackaged for profit. The dupatta isn’t in “every culture,” as some claim. The draped style clearly originates from South Asia. Scarves in other cultures are usually made of thicker fabrics, like wool, or styled differently.

Furthermore, the rise in South Asian – specifically Indian – hate has skyrocketed in recent years, both online and in person. The people are heavily discriminated against, but their culture is displayed on the fashion pages under a different name.

Just from 2024 to 2025 alone, anti-Asian hate online has risen about 66 percent, with South Asians bearing 75 percent of that hate, according to AAPI Equity Alliance. In the UK, violent mobs targeting brown individuals gained momentum throughout 2024.

Tensions were already high. For many people, these fashion brands’ actions were the final straw. That outrage was only stimulated more by non-South Asians claiming the fashion issue is “not that deep.”

The issue is deep with South Asians have been scared to wear their cultural clothes in public for fear of harassment. The issue is deep when almost every other aspect of South Asian culture is ridiculed online and in person. The issue is deep when so many luxury fashion brands exploit South Asian embroiderers for overpriced products.

Adapting items from different cultures and communities is the basis of human connection, but it is important to remember where many “trends” come from. South Asian women pride themselves in their cultural clothing.

Their fashion has contributed a lot to mainstream trends for decades. That contribution should be acknowledged.

South Asian women have taken to social media to call out the hypocrisy and exploitation of their culture by Western brands. Hopefully, their advocacy will inspire change and bring attention to the issue of cultural appropriation and cultural erasure in the media.