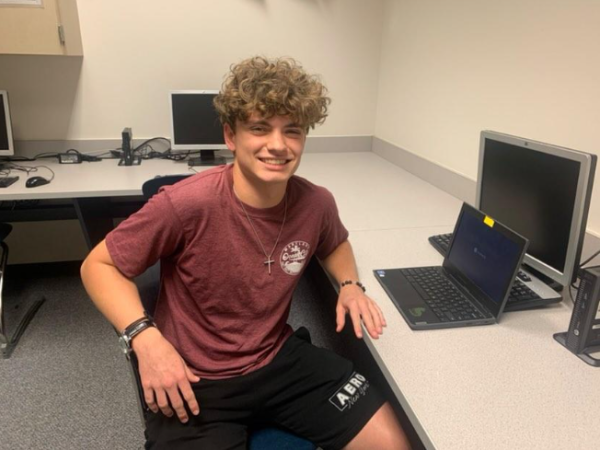

With the free time he had during the pandemic, freshman Carson Bender taught himself how to solve a Rubik’s Cube with a book from his mom, and he has been invested in competitive “speedcubing” ever since.

“I saw a video on YouTube of a compilation of all the Rubik’s Cube world records at the time, and it made me want to get into learning how to solve them. I wanted to be as fast as possible and learn all of the tricks. I like to memorize things and it requires a lot of memory,” Bender said.

Bender and his friend, freshman Hayden Fredrick, have developed their hobby to the point of competing with other speedcubers at large competitions.

The standard Rubik’s Cube is called a 3x3x3, which means that on each side of the cube there are nine squares of varying colors. The goal is to start with a scrambled cube and rotate the rows of the cube until the squares on each side are all of the same color.

Beginners might use trial and error to solve the Rubik’s cube, but there are algorithms, or a set of standard moves, that help cubers solve the puzzle more quickly.

“The solutions become automatic at a certain point. I recognize a pattern and then do an algorithm working from there,” Bender said.

Bender originally got invested in speedcubing when he was about 10 years old, and he has kept up with it for the last four years. He introduced Fredrick to the hobby that same year.

“After Carson introduced me to speedcubing, I learned from a video tutorial. From there I kept improving my method and looking into more advanced ones,” Fredrick said.

A benefit to speedcubing, Bender said, is that it’s a therapeutic hobby.

“If I ever get stressed with homework or something similar, sometimes I just take a break and cube,” Bender said. “It takes my mind off of work. But then when I’m done, I get back to what I’m working on. It makes my mind more relaxed, like a mental exercise.”

Fredrick’s main cube is a 3x3x3, but he also practices on “a Bluetooth cube that can connect to a phone app that tracks the cube’s movements and has a built-in timer.” Although Bender prefers to use the same 3x3x3 cube as Fredrick, he has also taught himself to solve a variety of other cubes and similar puzzles with different shapes.

According to NPR, 21-year-old Max Park of California set the world record for solving the 3x3x3 Rubik’s Cube with a time of 3.13 seconds at a competition last year.

Bender’s personal record is 17.70 seconds. Fredrick’s personal record is 32.2 seconds.

Hayden Ng, a spokesman for the World Cube Association, said the Baldwin freshmen are at a popular age for speedcubing.

“Most competitors are between the ages of 10 to 20 in most regions. That being said, the age range is wide, possibly ranging from 5-85 years old,” Ng said.

The popularity of competitive speedcubing seems to be growing. Last year “saw 2,135 competitions worldwide, and this number is projected to continue rising,” Ng said.

Bender and Fredrick have participated in competitions in Pittsburgh and other nearby states.

“There are usually only one or two competitions in Pittsburgh or even nearby cities each year. I’ve gone to one in Ohio and one in West Virginia,” Bender said.

Speedcubing competitions usually have three rounds, with judges making sure the cubes are properly solved. Bender and Fredrick have participated in three competitions each.

“I set some personal bests, and got to the second round a couple of times, which is something only the top 30 qualify for,” Fredrick said. “I’ve seen world record holders at these competitions before, but there are a lot of newcomers too.”

In mid-February, Fredrick traveled to Ohio for his first competition outside of Pittsburgh.

“The venue was a lot bigger than the Pittsburgh ones that I have been to in the past. There were a lot more cubers there. There were some people I recognized from local competitions, but it was mostly all new people,” Fredrick said.

Bender said he also made it to the second round of a competition, where participants not only compete, but judge rounds for others as well.

“It’s nerve-wracking sometimes because there are a lot of things you have to do at once, like solving quickly, running the cubes to the solvers, and judging for others,” Bender said.

In spite of the stressful factors involved, speedcubing events have a pleasant atmosphere.

“In general, these competitions feel like a gathering between a large group of friends. Most people are simply there to have fun and compete against themselves,” Ng said.

As with most things in life, practice pays off.

“When you know what you need to do in the situation, it becomes muscle memory,” Bender said. “I’d say I work faster because the adrenaline kicks in. Wanting to get to the next round makes me more determined.”